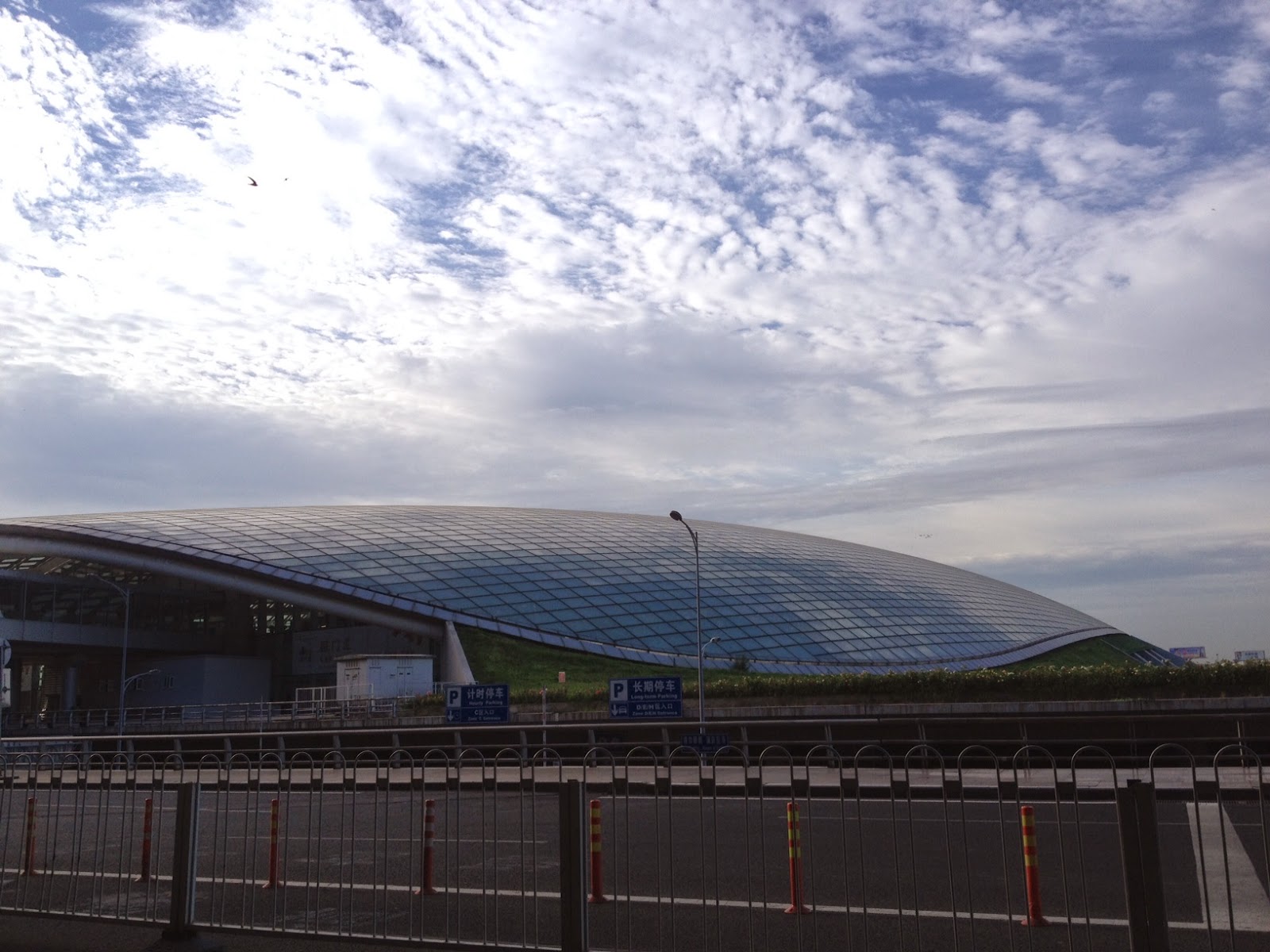

It’s now October. I recently revisited Beijing for a piece of fiction. I was trying to write my second-ever (poetry) piece for spoken word, but I keep getting caught up in the loping energy of long sentences, the way they move in compact bursts, and fold up like a loaded spring. I like sentences. I’ve come to know this about myself recently—during the last year of college I figured out that I was actually hopelessly confused about line breaks in poetry despite having taken so many courses in poetry and that instead I was confident in and curious about syntax, so it’s just happened that I return to the sentence when I really, really want to say something, or when something’s asking me to say it. So the subject matter of my spoken word piece will turn out to be something other than China, I believe.

I’m listening to Clair de Lune. I think I’d like to go back to the Temple of Heaven and just sit there, listening this way. While I was there I was reminded of the view from the Sacre Coure in Paris. You can just see…everything, but nothing in detail. And that kind of dual vision puts an auditory damper on everything, so it seems like it’s just you and that endlessness that was waiting for you there.

It’s difficult for me to write about my experience in China in direct words like I did for the first two Beijing posts you can see here. Instead, when I go to write about China I find myself immersed in the world I’ve created, safely apart, a distance precisely controlled and occasionally, purposefully, violated, of my characters. Last March, additional to the work I did for the short stories that I included in my senior thesis, I spent two days (nights, more truthfully) writing a three-chapter short story that I have, this summer, reworked and to which I find that I continually return when something about my experiences over the summer occurs to me. The story’s always had the same rough outline, which has always, even in March before I’d set foot in Asia at all, included description of Beijing. Now I just have the experiential memory to pad out (or, more often, completely change) the scenes I’d already written.

For example, the Great Wall of China. Thinking about this without having ever seen it, I thought it’d be maybe even fun to climb it. And I thought that, maybe, the word “climb” was just a word you had to use in conjunction with “the Great Wall” because it was a phrase, not because the actual activity involved … climbing. So when I wrote of it, I wrote of it wrongly. I forgot the most important things about the Great Wall in the summer—first, it’s over 100 degrees. Your skin is probably melting off your bones. People’s umbrellas are getting ing your face. Second, parts of it are nearly vertical tilt and required the use of arms as well as legs to ascend. You look like a monkey rambling up certain giant steps. Third—it is really, really, really high up. It’s in the mountains. As someone who is afraid of heights, I quickly found myself getting queasy looking down from the low heights to which I was actually able to climb. The hand rail was really low, too, so using it was more difficult than the weird crab walk you had to do to get down the stairs without using it.

For example, the Great Wall of China. Thinking about this without having ever seen it, I thought it’d be maybe even fun to climb it. And I thought that, maybe, the word “climb” was just a word you had to use in conjunction with “the Great Wall” because it was a phrase, not because the actual activity involved … climbing. So when I wrote of it, I wrote of it wrongly. I forgot the most important things about the Great Wall in the summer—first, it’s over 100 degrees. Your skin is probably melting off your bones. People’s umbrellas are getting ing your face. Second, parts of it are nearly vertical tilt and required the use of arms as well as legs to ascend. You look like a monkey rambling up certain giant steps. Third—it is really, really, really high up. It’s in the mountains. As someone who is afraid of heights, I quickly found myself getting queasy looking down from the low heights to which I was actually able to climb. The hand rail was really low, too, so using it was more difficult than the weird crab walk you had to do to get down the stairs without using it.  I didn’t write about any of that last March, during those midnights in which I imagined something flatter and less full of domestic tourists and walking upon which didn’t induce the types of exhaustion that it in fact turned out to. In my story there was too much chatter there, too much bodiless gazing out. I forgot the body. In fact the real experience was only and all about the body. The body’s interaction with culture, history, itself. For me personally it may have been metaphorical for the mental struggle I constantly re-encounter when I ask myself to justify my interest in a culture or set of cultures that doesn’t belong to me at all and the struggles to encounter the culture beyond its commodities, or the obvious. Still, though mentally I am pretty qualified to tackle these struggles, physically I am too afraid of heights and too weak and short-legged to have climbed high enough to reach one of those little stalls on the wall where you can purchase a plaque that says that you are a “real man,” now that you have climbed the Great Wall. Declaring that until you’ve climbed the great wall you are in fact, incapable of becoming a real man. It’s a comfort to me that I’m not, and have not been, concerned with becoming, or proving to anyone that I have officially become, a real man….

I didn’t write about any of that last March, during those midnights in which I imagined something flatter and less full of domestic tourists and walking upon which didn’t induce the types of exhaustion that it in fact turned out to. In my story there was too much chatter there, too much bodiless gazing out. I forgot the body. In fact the real experience was only and all about the body. The body’s interaction with culture, history, itself. For me personally it may have been metaphorical for the mental struggle I constantly re-encounter when I ask myself to justify my interest in a culture or set of cultures that doesn’t belong to me at all and the struggles to encounter the culture beyond its commodities, or the obvious. Still, though mentally I am pretty qualified to tackle these struggles, physically I am too afraid of heights and too weak and short-legged to have climbed high enough to reach one of those little stalls on the wall where you can purchase a plaque that says that you are a “real man,” now that you have climbed the Great Wall. Declaring that until you’ve climbed the great wall you are in fact, incapable of becoming a real man. It’s a comfort to me that I’m not, and have not been, concerned with becoming, or proving to anyone that I have officially become, a real man…. When we were first entering the landmark, there were a few nice areas to walk around and look out at the mountains before heading into the actual wall through the gates. While we were there I was approached by a boy with his parents. He didn’t speak any English but I understood that he wanted to take a picture with me. His dad made eye-contact with me that I will probably not ever forget and I don’t know exactly what he was thinking, but his son chattered something to him that made him take off in the direction of the gate without a glance back at us. My roommate for the trip managed to catch a picture of the picture-taking from a little ways off. After that the boy said more things to me in Chinese and I just nodded. He could have said anything. And then he asked to take one with my roommate, too.

When we were first entering the landmark, there were a few nice areas to walk around and look out at the mountains before heading into the actual wall through the gates. While we were there I was approached by a boy with his parents. He didn’t speak any English but I understood that he wanted to take a picture with me. His dad made eye-contact with me that I will probably not ever forget and I don’t know exactly what he was thinking, but his son chattered something to him that made him take off in the direction of the gate without a glance back at us. My roommate for the trip managed to catch a picture of the picture-taking from a little ways off. After that the boy said more things to me in Chinese and I just nodded. He could have said anything. And then he asked to take one with my roommate, too.

Several others asked me for photos while I was on the wall. Some didn’t even ask. Some wrapped their arms around my shoulders, some stood primly next to me. One young woman came out of nowhere and asked if I’d pose for a photo with her mother. The fascination of certain Chinese with foreigners is something about which I am still largely undecided. Of course fundamentally I will never understand the motivations: I grew up in a country of considerable diversity, while China, on the other hand, despite being comprised of fifty-something native races, is 95% Han…. So while I wasn’t thrilled at the attention, and while this experience has made me more wary of relocating to China for any considerable amount of time like one day, a while ago, I thought I might have liked to do, I can be amused about it, thinking back.

Opposed to this were the people who tried to carry on conversations with me in Chinese on the wall—when I was walking back down, alone, there was an old grandpa in a straw hat, to whom I’d motioned to use the handrail and had grabbed the sleeve of his jacket to move him over to the edge of the wall after he’d stood for a few seconds longer than necessary staring down at the next step…there were a couple groups of small children, one woman selling kites down outside of the gates, and the already-mentioned selfie-boy. Other than not knowing what to do while this was happening—just smiling and nodding if I thought I should—I found these encounters bizarre and kind of sad.

More than the Great Wall, I keep thinking and revisiting taxi rides, subway rides, walking miles and miles, a little lost, while sick, through the inner city and night markets. The peculiar and piquant scent of Beijing summers. The white dust in the inner city that falls from the sky like snow. And most of all I keep thinking about the Temple of Heaven, the gaze out from that place. Maybe because it was the first place we went, while everything was still new, magical, and yet while I was still waiting for this to feel like I was on the other side of the earth.